A Subtle Way to Tell Kids You're Gay

Truth be told, it feels unfair to have to come out to my students every year. In fact, last year, I didn't even do it because I was so exhausted by the process. And that's coming from me--the guy who works at a progressive school in the city of Chicago. I am and have always been accepted through and through, from the very moment I set foot in that building.

Despite this comforting reality, I still experience feelings of trepidation when I think about revealing to my students that I'm gay.After all, I believe it's important to come out to our students, no matter what my critics may say: they say they're unable to comprehend same-sex relationships; that it's developmentally inappropriate to teach about adult relationships; that they can learn about it when they're older and "ready."

But this is a very heteronormative way of thinking about adult relationships. It assumes that, because we, adults, overly sexualize same-gender relationships, that the children will, too. It is with our own homophobic baggage and discomfort with human sexuality that we project these fears of discussing same-gender relationships with our children.

Even as a gay man, I carry and project these fears, too

But I'm grateful to say that I learned something last week, when I came out to yet another group of students--albeit in an incredibly different way than I ever have before.

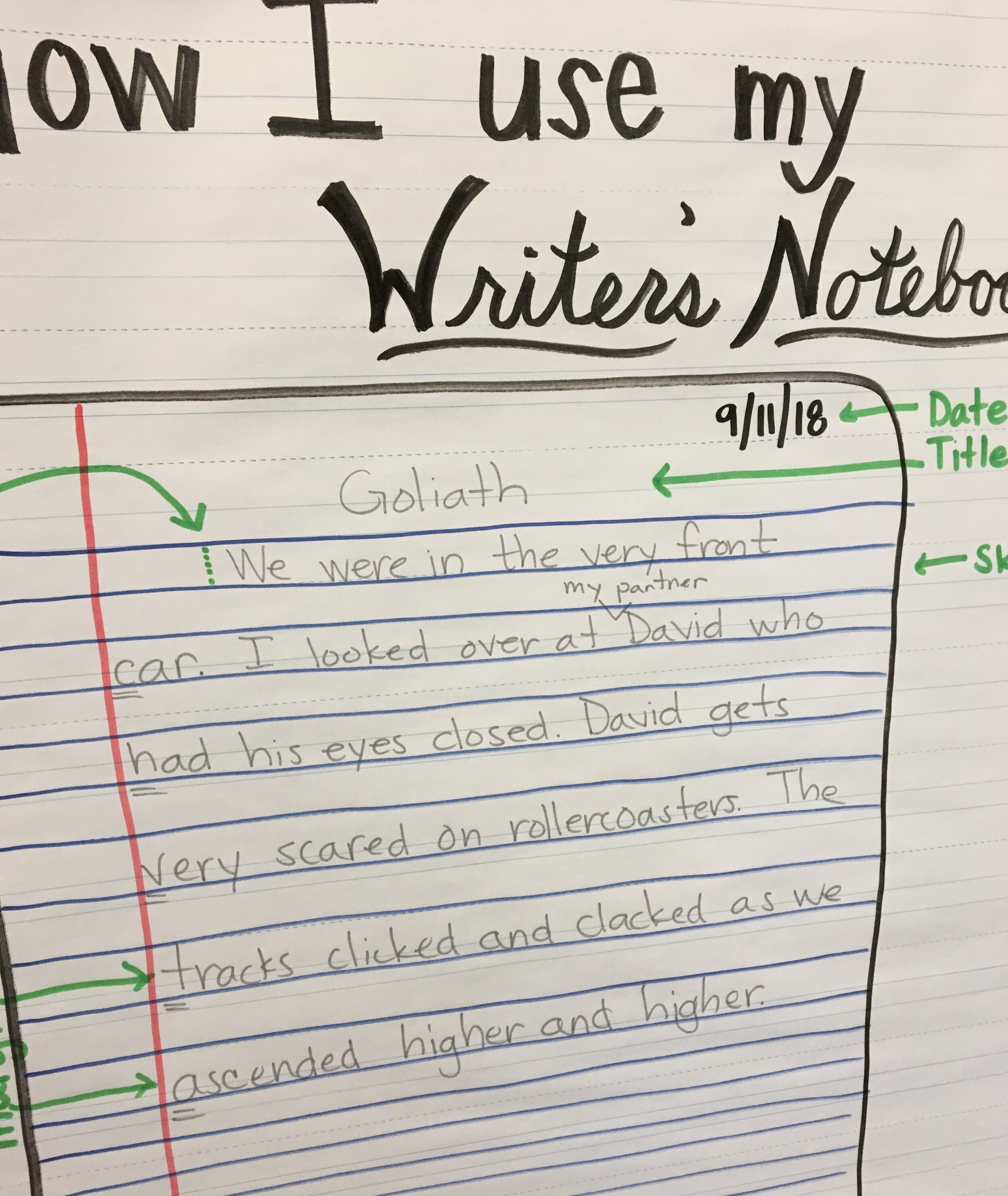

Our writing workshop lesson asked us to brainstorm a "small moment" about someone that we care for, all a part of Lucy Calkins's lessons on drafting small moments. Along with that, I was modeling for my students how to set up their writer's notebooks.

I made an anchor chart, and on it, I wrote the start of a small moment with my partner, David. As one would expect, students asked me--almost immediately--"Who's David?"

"Oh!" I replied. "Of course, I probably should clarify who my other character is."

I inserted a carrot and wrote the words: my partner.

Writing our identities into stories is one way to normalize them.

"David is my partner," I continued.

"What's a partner?" one student blurted out.

We're still working on raising our hands.

"Well," I began thoughtfully and intentionally, "a partner is kind of like how two parents are together--kind of like your moms and dads. It's two people that really love each other that share their lives and do things together."

There was a slight pause, as I'm certain this was a slightly new idea for some of them.

"Thank you for asking that," I replied. "It's important when we write we consider our audience. We need to clarify who our characters are. Don't forget to raise your hand next time."

I winked, And we moved on

In this anti-climactic moment, I learned something incredibly valuable. As the question was asked, I felt my heart beat just a little bit faster, my face get a bit warmer than it was just seconds before. But I went into the lesson with the intention of normalizing, and I took that with me in this moment where my anxiety kicked in.

Too often, these situations are so emotionally charged and uncomfortable not because of our students: they are so because of us. We are the ones who have been conditioned to be uncomfortable with that which makes us unique. We are the ones who project discomfort, shame, and trepidation onto our kids. And in the process, we only make it worse for ourselves.

On that day, I came out to my kids once again, but this time, it was entirely different. Instead, coming out to my students ended up feeling no different than telling them that I like cheese pizza or that I like to write in my spare time. It didn't stop them in their tracks or derail my lesson. While it captured their attention, I like to believe it's only because they learned something new about me, something that allowed them to humanize me in a way that hadn't yet been able to do.

Straight, cisgender skeptics will say that this was a poor choice--that we don't and shouldn't teach about adult relationships in schools because students aren't ready. But this is untrue and inaccurate. We teach about adult relationships everyday--from the Mrs. before a married female teacher's name, to the pictures of their families that we hang in our classrooms. And we should do this, not in an effort to sexualize our children prematurely, make them uncomfortable, or push any sort of agenda. We do this because it's important to teach our children that love exists in all forms.

Especially in our current world, children need to know that love is ubiquitous, ever present, and not to be judged. And they are capable of this, most of all, because they themselves are conditioned to know, feel, and spread love.