How to Welcome the Asexual and Transgender Communities into Your Classroom

This week, we welcome Ace, a teacher from Maryland. Ace uses children’s literature and inquiry to actively welcome the asexual and trans communities into their classroom. Thank you, Ace, for sharing your story with us.

Conversations about sexuality and gender are extremely important for our students, and they can also be intimidating and stressful, especially if your school isn’t as open as you’d like. Sometimes, LGBTQ+ topics feel like whispers in the hallway; forbidden conversations that are saved for parents to deal with at home.

It’s time for that to change

My name is Ace. I was born with female anatomy, but I knew at six years old that I was not a girl. I tried my best to get my parents to call me “Colt” (I was obsessed with Three Little Ninjas.) and let me wear boy clothes, but they didn’t budge. To them, I was Amanda, and I belonged on the female end of the gender binary along with dresses, bows, and pink. But to me, I felt like a stranger in my own body, and I had no idea how to handle the emotional dissonance going through my head. So, I did what made sense for me at the time: I pushed all these feelings down and didn’t think about them again for fifteen years.

When I was in college, I discovered terms like asexuality (no sexual attraction to anyone), and that felt like a really nice fit for me. Dating had always been a struggle because I never seemed to be able to reciprocate more intimate feelings. Learning about asexuality made me feel less alone in the world. Then, during my second year teaching, I finally began to reconcile the gender dysphoria I had been hiding for more than half my life. It took some trial and error (and lots of love and patience from my friends), but I finally feel confident in my identity. I now go by Ace, and I identify as non-binary. Next year, I plan on transitioning to Mx. Schwarz and using they/them pronouns with staff, students, and parents. As I look back on my educational career, I think about all the teachers I admired. I wish they would have known what I knew now, because I think if they did, they would have taken more time to talk about gender and sexuality in the classroom. I spent years thinking there was something wrong with me because I didn’t have the vocabulary to explain how I was feeling. Sometimes, I get sad about all the time I spent hating my body and my gender, but it also motivates me to do better for my students.

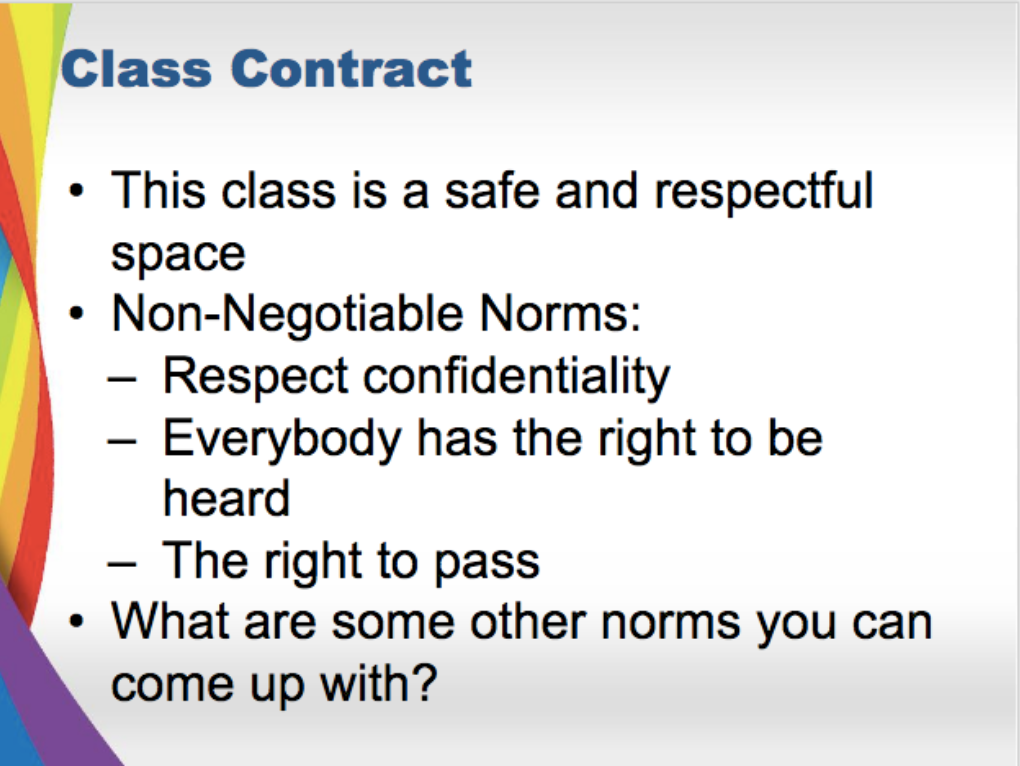

The most inclusive way to begin conversations about gender and sexuality is through storytelling. Stories allow for infinite truths to co-exist in the same space. I am privileged to have a supportive administration, and they have worked with me on incorporating more LGBTQ+ topics in my curriculum. My school has a TIE (Targeted Intervention and Enrichment) class, which is known as our “skinny period.” Students who need intervention get additional help, and those that don’t go to an enrichment class. As an enrichment class this year, I piloted the book Gracefully Grayson by Ami Polonsky with one of our school counselors. In the story, we follow Grayson, who was born a boy but realizes that he identifies as a girl. The book explores his struggle with identity and his transition from male to female. I highly recommend reading the book because as someone who also wrestled with identity, I felt that it accurately presented both Grayson’s struggles and triumphs. My one critique is that Ami Polonsky is a cisgendered female, meaning her gender identity matches the sex she was assigned at birth. Therefore, she wrote Grayson’s story without completely understanding his/her experience. The book made talking about gender and sexuality natural, as it should be. We started by looking at what identity means, and we drew Grayson as he saw himself in the beginning of the book and updated this picture over time. As we read, I defined vocabulary such as transgender, gender non-conforming, ally, etc. Students journaled about Grayson’s experience and related it to their own lives. We even held a Socratic Seminar about labels, and students blew me away with their honesty and willingness to share about their own identities. It wasn’t just the book itself that created space for these courageous conversations: we developed classroom norms on the very first day of the book study that helped make my room a safe space for students to ask questions and participate fearlessly.

But the learning didn’t stop just because we finished the book

Afterwards, we used resources from the Gay, Lesbian & Straight Education Network (GLSEN) to supplement further learning about gender and sexuality. Students researched pride flags and created their own identity maps. Currently, we are currently wrapping up a timeline project about LGBTQ+ history. I plan on hanging these timelines outside of my classroom, and my class is really excited to provide this kind of visibility to other students. I teach about 135 students total, but there are only 22 in my Gracefully Grayson class. But there are so many more students who do not have access to these types of experiences. I knew I needed to do something to not only show my support for LGBTQ+ students, but to make the LGBTQ+ population more visible in my school.

Enter my pride wall

The pride wall is visible to my entire classroom and the hallway. I never explicitly said anything about the wall when school started, but I never had to because students came up with questions on their own.

“What do all the flags stand for?”

“Why are there so many different flags?”

“How do I know which flag I am?”

“Which bathroom does someone use if they don’t identify as any gender?”

These are just four of the many questions I’ve gotten because of the wall. Students are naturally curious, and I do my best to answer their questions without disrupting class. Sometimes, I wait for students to be working independently to answer a question, while others are worth answering for the whole group. I don’t bring any politics into the answers, and I make sure the answers don’t detract from the science content I am teaching.

Boundaries are important, but I also believe in answering all student questions and ensuring that their voices are heard

I realize not all teachers work in an environment that is supportive like mine. This means that those who do work in supportive environments have the responsibility to ensure students are exposed to topics like sexuality and gender in informed and non-threatening ways. This may seem like a tall, intimidating order, but you never know who needs to hear that conversation. You never know who is struggling with their own identity and needs to hear that their feelings are valid. Our students are so unique, and we owe it to them to provide an education that is well-rounded and honors that diversity.

Share this story with all those who need to hear it, and if you want to share your story, reach out to Paul through the comments or on Instagram or Twitter (@paul_emerich).