How to disrupt conversations about learning loss

Conversations about learning loss are going to happen in your school. It’s inevitable. And while it may be tempting to lean into the myths of learning loss, or perhaps even dismiss these conversations entirely, engaging with these conversations—for the purpose of disrupting them—may be your best bet.

To disrupt conversations about learning loss, we must have conversations about equity, and by proxy, we must have conversations about identity. Learning loss is not really a new idea; it’s simply a re-branding of deficit-based thinking about teaching and learning, more recently known as “the achievement gap” and dating back to the Reagan-era framing of the education system in “A Nation at Risk.”

This framing of teaching and learning is undoubtedly steeped in white supremacist and patriarchal thinking, which is why our approach to returning to school in-person must be conducted through an equity-focused lens. We must be keenly aware of how a deficit-framing of learning will harm students.

A conversation like this can easily get heated because, well, equity is personal. When discussing equity, we inevitably discuss identity. While discussing identity can be validating for those who experience marginalization (People of Color, LGBTQ+, People with Disabilities, femme/female), doing so might also cause those with dominant identities (white, cisgender, heterosexual, male) to feel uncomfortable.

In “Speaking Up Without Tearing Down,” Loretta Ross shares the value of “calling in.” While she states that calling in may not be appropriate in every situation (i.e., cruel/careless language, intentional violation of civil conversation, violence), it can be helpful in preserving relationships, helping all parties move forward together, and leveraging those feelings of discomfort as opportunities for learning.

Trying to disrupt harmful conversations about learning loss? Give these three strategies a try.

Strategy 1: Ask Lots of Questions

When someone in your school invokes “learning loss”—or perhaps even the newest branding of learning loss, such as learning acceleration, learning recovery, or learning leaps—we need to start by gathering more information. While these questions will likely not change your opinion on learning loss, they may give you more information on how to reframe your colleagues’ thinking.

You may want to ask questions like:

Tell me more about how you’re defining learning loss.

What are your goals with accelerating learning?

What evidence are you using to decide learning has been lost?

Are you familiar with the term deficit-based?

Is it possible that the notion of learning loss is grounded in fear?

While asking questions is a great strategy, it can’t come from a place of self-appointed intellectual superiority. It has to come from a place of genuine curiosity. You have to truly want to understand your colleagues’ ways of thinking—as well as what has contributed to the formation of that thinking—in order to meaningfully connect with them through this type of discourse.

In my experience, disingenuousness is palpable. Your colleagues can sense when you are asking leading questions merely to disprove them, versus meaningful questions to better understand their thinking.

Strategy 2: find points of alignment

After asking these questions, it’s entirely possible you will find more differences than similarities between you and your colleagues’ thinking. But I wouldn’t lose all hope. The reality is this: you need to find common ground to work with your colleagues, and by looking for the places you align, you may be able to move the conversation forward.

The end of the school year, the summer, and the start of a new school year are great times to have conversations about pedagogical values and vision. Especially now, as teachers across the country are reeling from an exhausting year, structured discussions around what worked, what didn’t work, and what to change will be both productive and therapeutic.

I use a few structures to promote collaborative dialogue on my teams:

Carousel

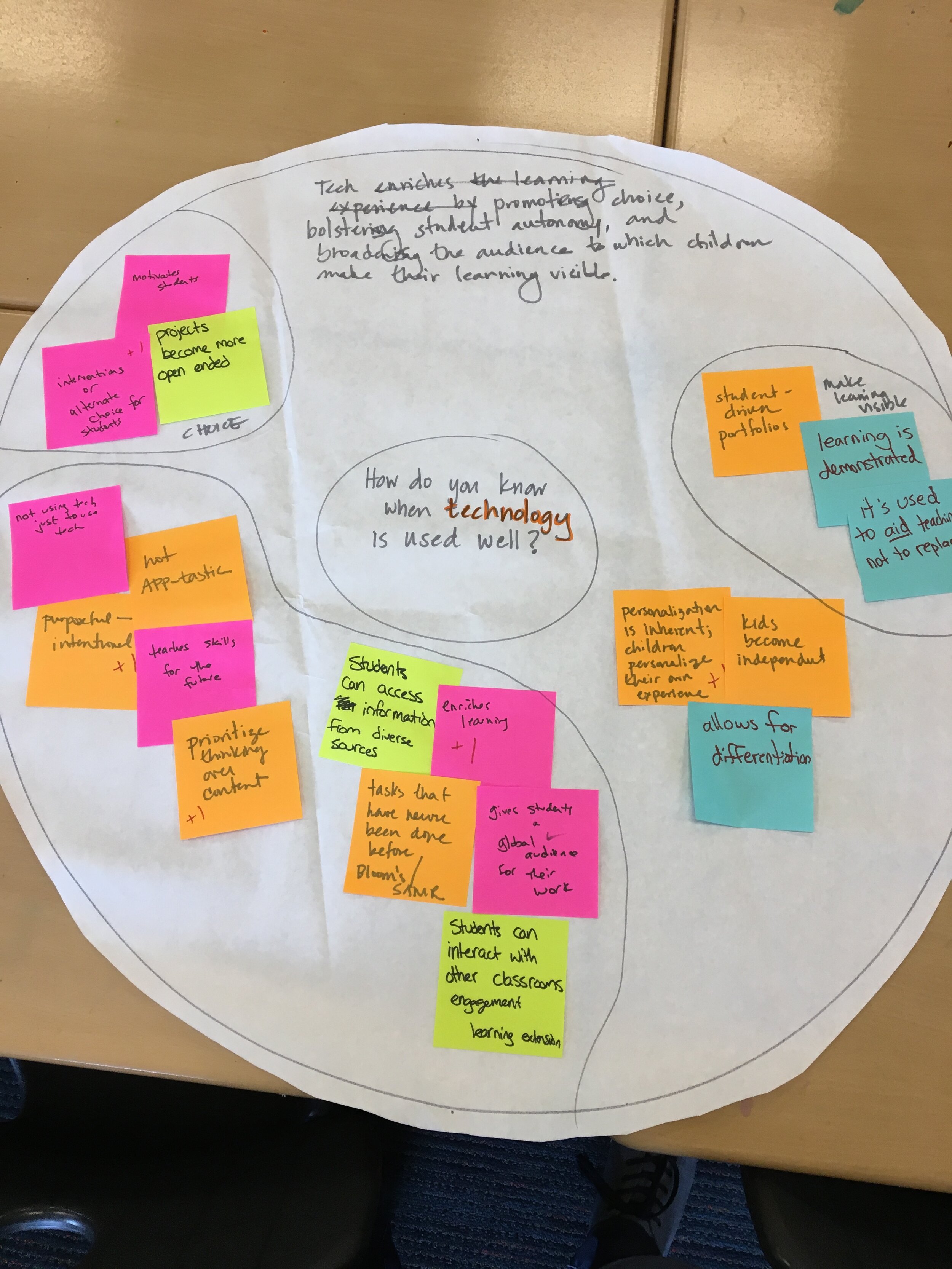

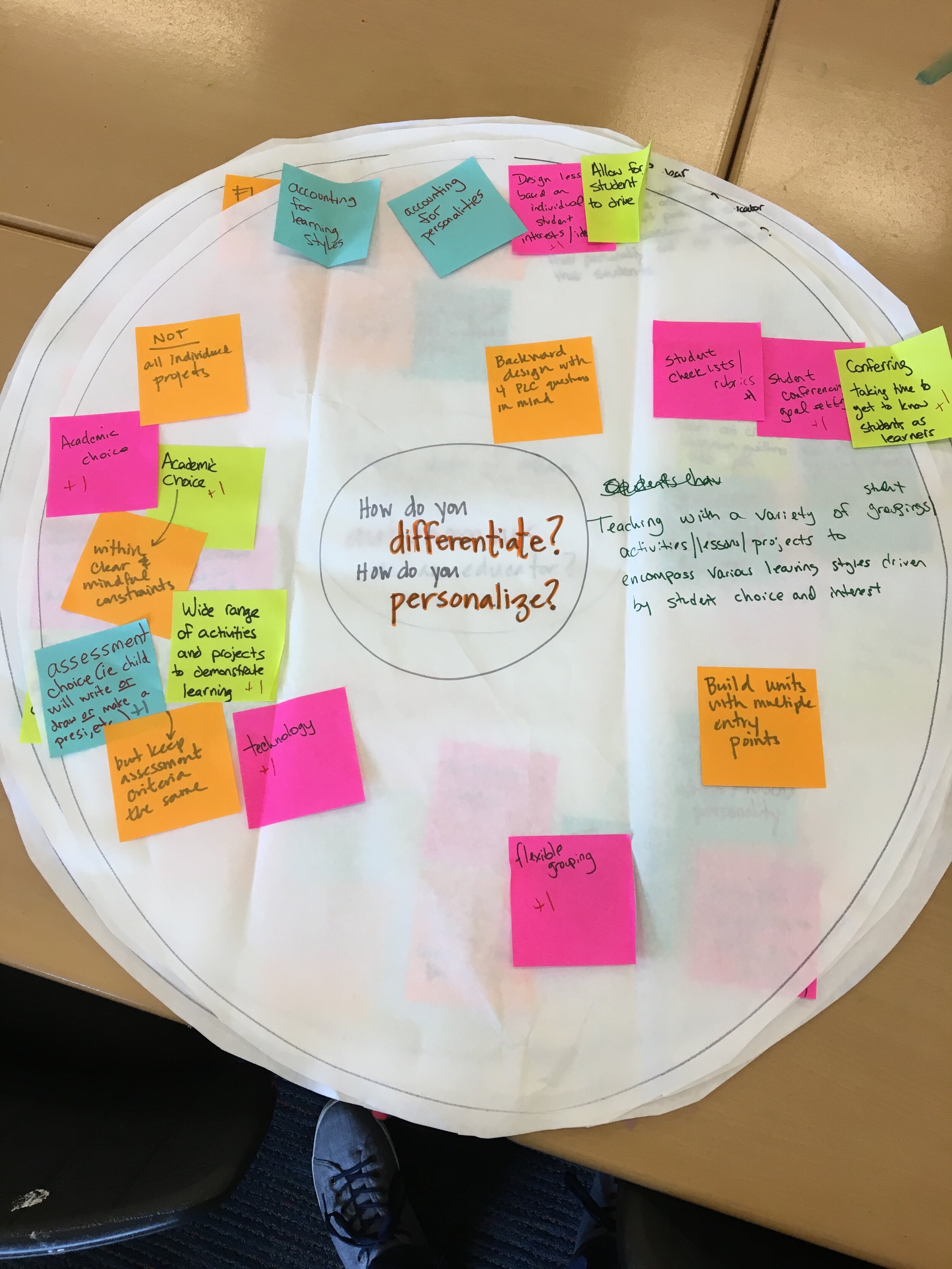

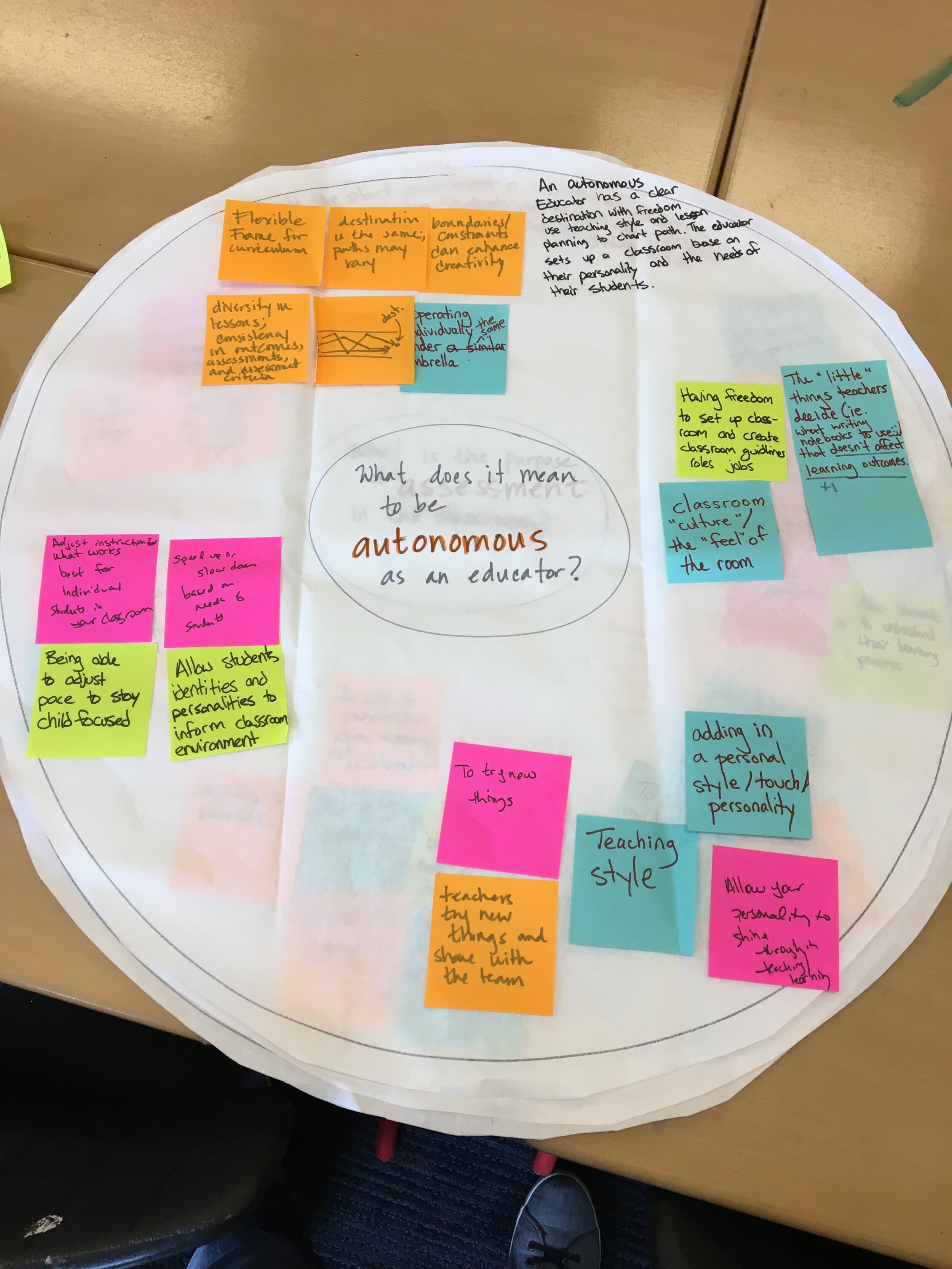

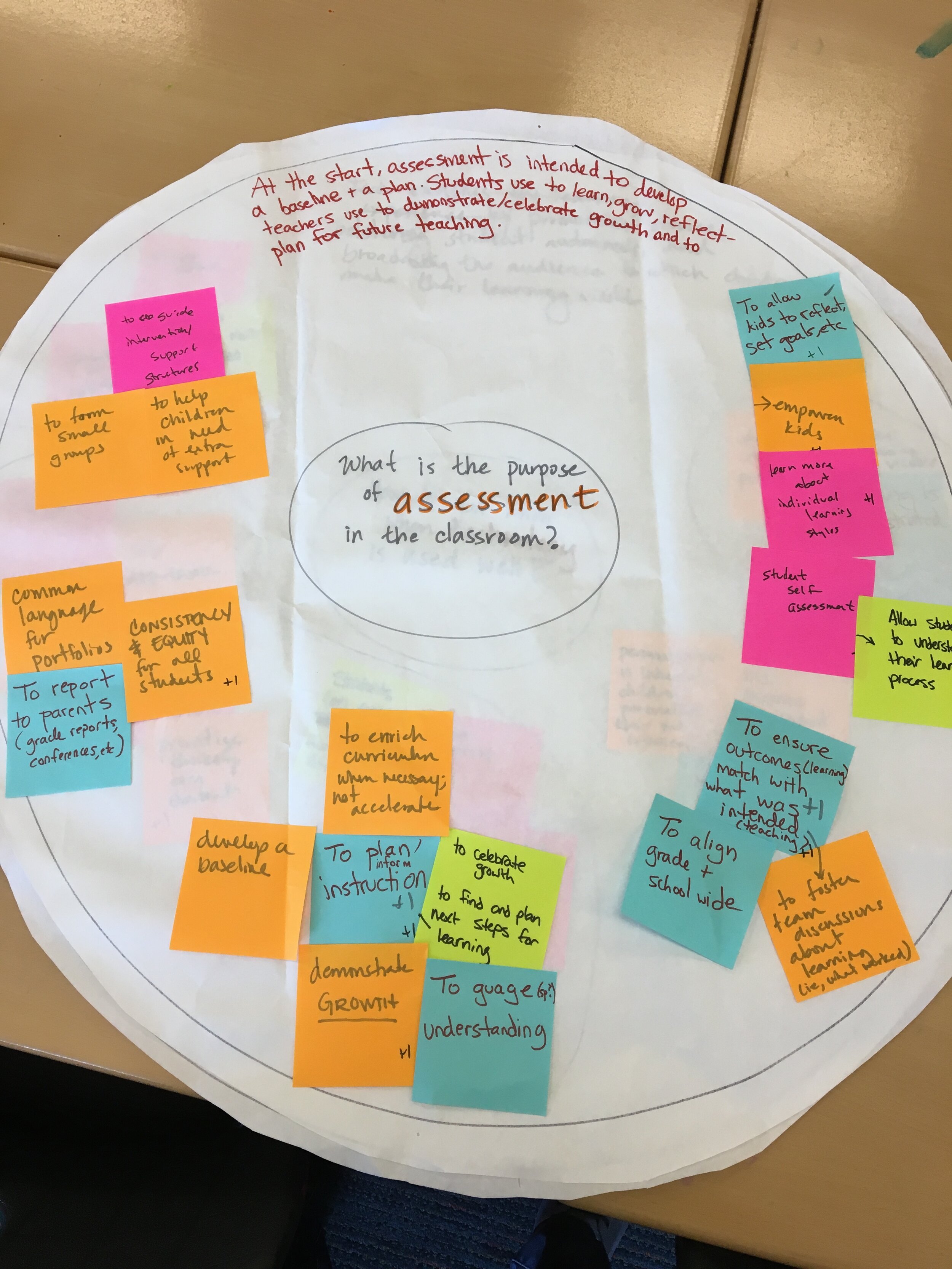

Carousels are great for brainstorming and collecting ideas. A few years ago, I was leading a new team, and I knew it was important for all of us to come together around a common vision. To build this vision collectively, we answered four questions, and used our answers to build collective vision statements related to curriculum, assessment, pedagogy, and technology integration.

Compass Points

Compass Points comes from Project Zero, and is featured in Making Thinking Visible. This thinking routine could serve as questions for your carousel, or become an entirely different vision-building activity with your team. Finishing a year of pandemic teaching will undoubtedly come with worries and fears for next year, but it will also come with feelings of hope and opportunity. When planning for next year, we should be holding space for all of these feelings—and a routine like Compass Points can do that.

Compass Points uses the four points of the compass: north, south, east, and west, posing questions that align with the acronym NSEW:

What worries you about returning to school in-person?

What excites you about returning to school?

What needs do you have as we return to in-person learning?

What suggestions for change do you have as we return to in-person learning?

It’s highly likely that learning loss (or words and phrases that are symptomatic of this deficit-based way of thinking) will end up in your list of “worries,” and while these worries are real and valid, contextualizing them with feelings of excitement and hope may be helpful. It’s possible that the opportunity to reimagine pieces of the curriculum or a particular way of teaching may overpower fears of learning loss, very much so disrupting the centering of learning loss, and instead, reframing the conversation around what really matters as we return to in-person learning—healing, engagement, and an asset-based framing of what our students are bringing back into our classrooms after a year of living through a pandemic.

Strategy 3: Play the long game

You won’t change someone’s biases in one conversation. Trust me, I’ve tried. But you might make gains by investing in the relationship. The reality is this: someone who is invested in and connected to the idea of learning loss is much more likely entangled within a way of thinking grounded in white supremacist and patriarchal schooling. Educators who live in this paradigm have been conditioned to believe that their success is determined by quantitative data and the relative pace of learning in their classrooms. Breaking oneself of this mindset is a long and arduous process—and the uncomfortable truth is that you may not get as far as you’d like in one conversation.

Instead, make it your goal to get to the next conversation. Delay your own gratification, and reframe your own definition of success with these conversations. Success doesn’t have to mean radically changing your colleagues’ minds over night. Success could, instead, be creating a collaborative space where your colleagues want to come back and engage in critical debates with someone who thinks differently than them.

And we sure could use more spaces like those in our schools.