Helping Students Find Their Words

“I’m bored,” said my student—A phrase I hear all too often

“Oh, yeah?” I replied. “What makes it boring?”

“It’s just boring,” he continued indignantly.

“Well, if you can’t tell me what’s boring about it, I can’t help you,” I said, playing my next card.

“It’s too hard,” he replied.

“Ah, I see,” I continued, perpetuating the conversation. “What makes it so hard?”

“Paul, poems are supposed to rhyme,” he said back to me. “I can’t make this poem rhyme.”

“Oh,” I said back, “there are lots of poems that don’t rhyme!”

I brought both boys in the group to the wall, where they were able to see a couple of the examples some of my students had already completed. Their assignment was to create a poem in response to the two statues at Washington D.C.’s Holocaust Museum. The first statue was intended to resemble an upside-down black house, while the other was intended to resemble the rebirth after the Holocaust. Of course, my students did not know this. I had withheld the context from them in an effort to keep their minds open. It wasn’t until later in the week that I shared the original intention of the sculpture with them.

“See? Poems don’t need to rhyme,” I said to them, referring to the three student-created mentor texts already posted in the room. “These poems are awesome, and they don’t rhyme at all!”

I led them back to their sheet of paper and began to facilitate their poetry writing. They still seemed like they were at a standstill. Their creative juices were not flowing. I stopped, and I wondered about the root of the problem. These were both two very intelligent young boys. Where was the creative block?And then I remembered. Sometimes, a student’s blockage isn’t necessarily there because they don’t know what to do: instead, a student’s blockage comes because they don’t know how to communicate it.

Because they can’t find the words

In fact, the difference between a student’s ability to identify and define words versus recall them is quite different. These skills, while complementary, are entirely different. One requires observation and connection, while the other requires long-term memory, articulation, and eloquence. And truth be told, a lot of kids aren’t ready for that.

“Let’s try this,” I said, pulling out some post-it notes and a magic marker. “What do you see when you look at the images?”

“Black,” the first student said.“Great,” I replied, writing down black on a Post-it note. “What else?"

“Unbalanced,” the other added.

“Awesome, I can see why you think that,” I said, writing down unbalanced on a Post-it note.It wasn’t long before we had a whole slough of Post-it notes placed in a pile on the paper. By doing this, I had scaffolded the instruction just enough to help them conquer the obstacle of word recall. I didn’t give them the words; I simply gave them a way to get the words out.

“Now, what I want you to do,” I continued, “is arrange these words in a way that makes sense to you. Feel free to add some words if you need to.”

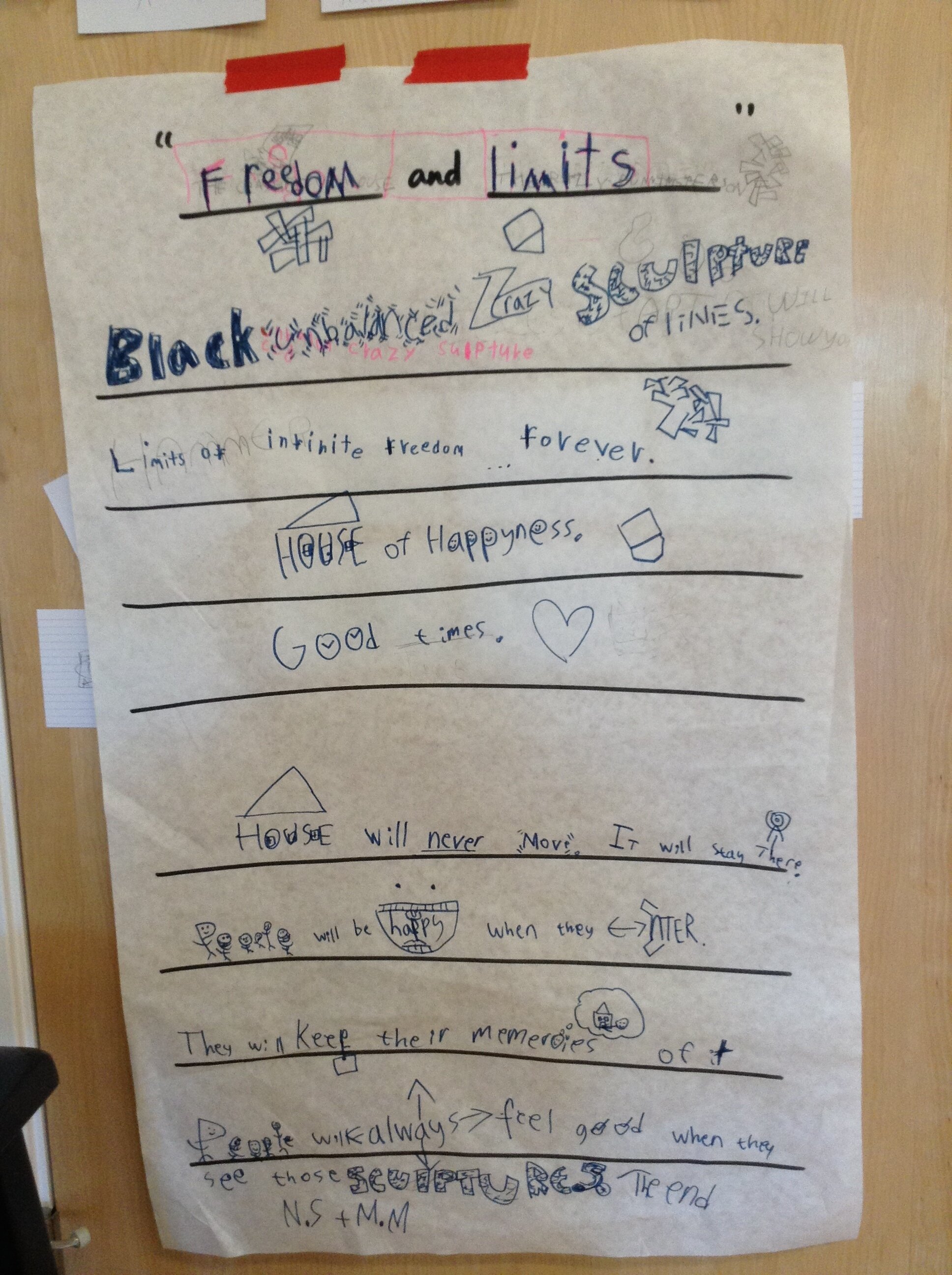

When they were done, they had a piece of poetry that truly represented what they were capable of. Check it out:

“Freedom and Limits”

Black unbalanced crazy sculpture of lines

Limits of infinite freedom… forever

House of happiness

Good times.

House will never move. It will stay there.

People will be happy when they enter.

They will keep their memories of it

People will always feel good when they

See those sculptures.

This would not have been possible had I not given them the tools to get their thoughts out. All too often we accept "I can’t do it" as either failure or giving up, when in reality, it’s just a matter of identifying the blockage and helping our students find their path to the goal.